Hoarders or archivists?

our immigrant parents & "clutter" as testimony

On a recent trip to a bookshop, I picked up Seeing for Ourselves: And Even Stranger Possibilities by Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan. While my bag weighed heavy with a pick of new books to start, it was the deep blue cover, gold text and lines circling into the eye of a storm that I reached for.

Suhaiymah writes in a way that moves the heart and mind. She holds the critical and personal close, her words reverberate beyond closing the book. I’m having that exciting experience: reading a book and feeling that I will be changed by the time I reach the final page. I might share longer reflections about Seeing for Ourselves in future but I’ve already found such the wisdom and food for thought in the mere 46 pages I’ve read so far. Through poetry, vignettes, essays and memoir, Suhaiymah thinks through history, memory, objecthood and subjecthood, performance, and what could be beyond the desire ‘to be seen’. But in today’s newsletter, I’d like meditate on her writing about ‘clutter’.

At the start of the second chapter, ‘the want / how I find myself,’ Suhaiymah writes:

“The nineteen white IKEA boxes in my room cause me shame. When they are made visible by a friend curiously asking about their presence, I make a joke of their existence. I hide the seriousness of their aspiration behind a self-deprecating comment about being ‘a bit of a hoarder’. More truthfully, every note in these boxes, every school exercise book, worn birthday card, torn letter, faded journal, scrawled-on envelope, unreadable receipt and ancient bus ticket is a type of evidence I cling to. Scraps of life and bureaucracy that bear witness to my living. Evidence I have existed.”

And on the following page:

“My mother fears her bedroom is full of clutter. In reality, it is full of proof. We joke that she carries a filing cabinet around in her rucksack.”

I suspect many of us who grew up as the children of immigrants can attest to the ‘clutter’ that filled our homes. Newspaper cuttings. Tupperware boxes. Ice cream tubs. Church pamphlets. Plastic bags folded into another plastic bag. Buying two or three of something when one will do. More pots and pans than you can count. The good cutlery and china. Traditional cloth covering the leather sofa, protecting it from the oil in our hair. Lists on backs of envelopes and post-it notes. Notebooks filled with reminders and to-do’s, kept even when all has been done. Shirts and socks and trousers and laptops and televisions in boxes, or sometimes exposed and gathering dust, saved for when they would be sent back home.

Of course, when we had visitors, this would all be hidden in a humble crate or few. There was nothing like the panic of an unexpected visitor to send us into action. Crates and boxes would be filled and tucked away within minutes. I would wonder if our guests could hear my parents’ breathlessness as they said hello, see the relief as they welcomed them in. I would be upstairs or in the furthest room hiding the last of what my parents couldn’t get to before myself emerging, readily composed. We would often laugh after they left, admiring how effectively we could hide the clutter, our life and way of living. As a child I remember visiting the houses of my white friends and wondering, if their houses were tidy, if they were always this way, or, if they were messy, how they hadn’t thought to tidy up for my arrival, as I would have done for theirs.

In Gwendolyn Brooks’ Maud Martha, set in 1940s Chicago, a white boy is due to visit young Maud at her family home and while she cleans, she sees herself through the eyes of this boy: “Maud Martha looked the living room over. Nicked old upright piano. Sag-seat leather armchair. Three or four straight chairs that had long ago given up the ghost of whatever shallow dignity they may have had in the beginning looked completely disgusted with themselves and with the Brown family.” Here too, the feeling of shame and embarrassment permeates what it means to see one’s life and way of living through the eyes of another. In the act of tidying and clearing ourselves away for visitors, we replicate tools of survival we use in the outside world in the domestic realm: how can we make ourselves presentable, inoffensive, easier on the eye?

As Suhaiymah invites us to consider, the receipts and envelopes and cuttings and pamphlets are more than “mess” or “clutter”: they are a manifestation of proof and evidence of self. It’s why it is so vulnerable for our belongings to be seen and potentially dismissed as “mess”. Here, in this clutter, is who I am and who I have been. It is a long tail of history and testimony, when official records will give us neither. I think about my parents, the parents in our communities, who grew up without the opportunity to accumulate. To see themselves in boxes upon boxes of life, however faded or illegible or unopened, it to be a witness to their memories and journeys. As Suhaiymah writes: “Their existence…is what we clutch to. Rarely do we look at them, but the thought of losing them is too much to consider.”

A friend - a child of Ghanian immigrants - and I once spoke about moving out and the choices we were making now we lived independently. We spoke about being drawn to the congruent - a home that has been thought through rather than patchworked together with different patterns and eras. A home that quietens rather than overstimulates the mind. A home where there is be a place for everything, where we won’t have to resurrect our belongings from boxes and crates. But my resemblance to my parents is in the blood. However hard I try, I keep receipts of dinners with or gifts I have bought loved ones. I keep birthday cards and hold onto clothes I have outgrown out of sentiment. I don’t know how to keep the memorabilia of my life in a coherent way and perhaps that is the most honest way these items can be kept, unwieldy and brimming with life, even as they are hidden in drawers and cupboards. And even when I visit my parents now, my senses are quieter. There is an ease that comes in knowing all this “clutter” is really a testimony of life.

Wonders This Week

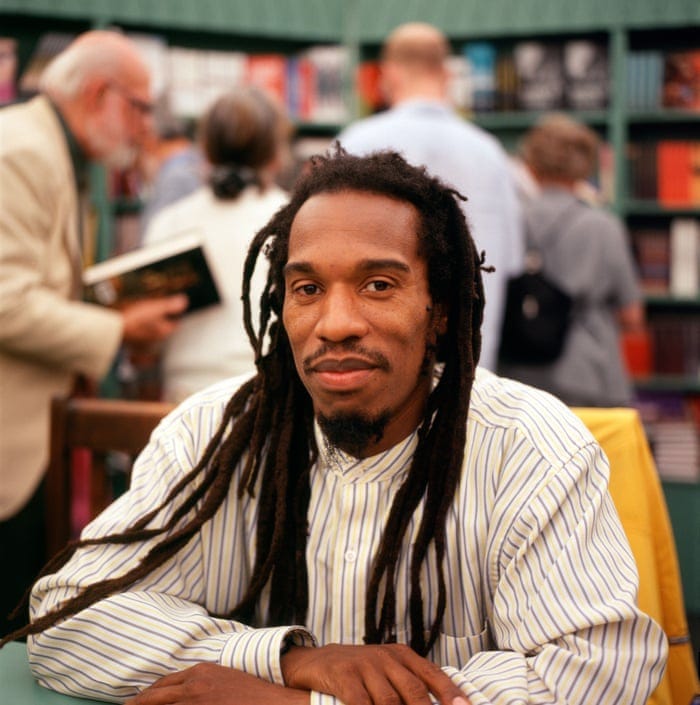

Benjamin Zephaniah. One of the literary greats passed on earlier this week. Growing up, I remember his books Talking Turkeys and The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah on the bookshelf at home. I remember how highly my dad spoke of him. He was always a reference point, perhaps in ways I couldn’t articulate back then, that you could be Black and make a career from words, that words could be powerful and help to make meaning in the world. I’ve learnt new details about his life in recent days, including his wish for children, his grief at being unable to have them (paywall), and how this informed how he loved in life; and, his regret at being occasionally violent towards previous partners (Vanessa Kisuule has an excellent thread on integrity and how perpetrators of violence can reckon with the harm they have caused). The outpouring of love has been beautiful to see and I hope Benjamin knew how loved he was, and is.

Finding refuge in books. I was in need of comfort this week and found myself in a bookshop on Friday night reaching for the words of writers and poets. Bookshops and libraries will forever be wonders to me; since I was a child, these places have felt like home (here are two great essays by Lola Olufemi and Zadie Smith on libraries). Leaving with a bag full of books, I felt satisfied. On the train home, my heart was already calmed opening the first pages of a book (Suhaiymah’s book actually!)

Wonders This Week has been word/literature heavy and it wouldn’t be complete without including my dear friend and sister’s excellent newsletters. Isabel writes Quality Sheet and Colouring Outside the Lines, which bring me great joy each week. Like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re going to get - but it’s always sure to be delightful.

I hope you have a wonderful week - Sarah x